Writing skills offers advice on writing in an academic style suitable for essays and assignments, and practical guidance on how to structure ideas and improve written work.

Sample activity: Outline the key characteristics of academic writing

How is academic writing different from posting a social media update or sending a message to a friend?

Most academic writing has certain features and conventions in common. These features relate to the way in which you:

-

Use evidence

-

Develop a line of reasoning

-

Support your opinions

-

Guide your reader towards your conclusions

Module content

Writing skills features the following:

- Diagnostic test

- Section 1: Academic writing

- Section 2: Planning your writing

- Section 3: Developing your writing

- Section 4: Improving your writing

- Section 5: Writing for different subjects

- Module assessment

See what’s in each section below:

Outline the key characteristics of academic writing

How is academic writing different from posting a social media update or sending a message to a friend?

Most academic writing has certain features and conventions in common. These features relate to the way in which you:

-

Use evidence

-

Develop a line of reasoning

-

Support your opinions

-

Guide your reader towards your conclusions

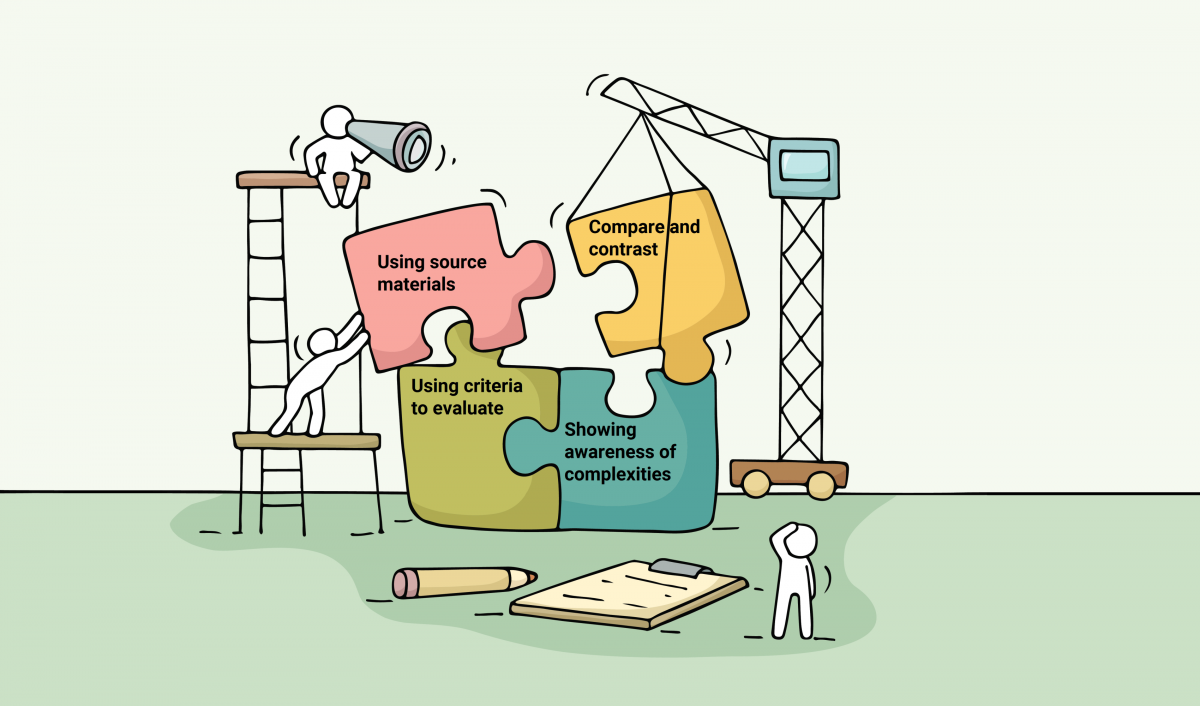

Using source materials

In academic writing, it is not sufficient simply to state your personal opinion. Instead, you are expected to present material from reading, lecture notes and other sources, and use evidence, examples and case studies to develop reasoned conclusions and justified opinions.

Comparing and contrasting

Most academic assignments require that you compare and contrast items – typically theories, models or research findings. You will usually be expected to read different views and to weigh one against another.

Using criteria to evaluate

In academic writing, you are asked not only to evaluate evidence but also to state the criteria you have used as the basis of your evaluation. For example, you might say that you trust particular figures because they are the most up-to-date or drawn from the largest available survey, or you might give weight to a particular expert’s opinion because she is drawing on a large range of well-conducted experiments.

Showing awareness of complexities

To demonstrate your command of the subject, you need to show that you are aware that conclusions may not be clear-cut. For example, in writing about teenagers you might quote an expert who has conducted influential research with young children, but in your commentary you might question whether the results would also apply to teenagers. By acknowledging weaknesses in your own argument and strengths in opposing arguments, you demonstrate that you have considered the matter objectively. If there is difficulty in coming to a firm conclusion one way or another, state clearly why this is so.

Presenting an argument

In your writing, show a line of reasoning. Make sure that one point follows logically from another, so that your readers can follow your argument and understand your conclusions.

Taking a position

At the end of your writing, state which side of the argument, or which model or theory, you find most convincing. Even if arguments are well balanced on either side, it is important that you show that you can come to a decision on the basis of the evidence.

Following a set structure

In your particular subject area there is likely to be a set structure for the type of writing required, or a particular style; if so, you need to follow this.

Despite such differences, however, all academic writing requires that you gather related points together in one paragraph or section (rather than scattering them throughout the text).

Arguing systematically

In academic writing, link your points together to form coherent sentences and paragraphs, with each paragraph following naturally from the previous one. Each new point should contribute to your central line of reasoning, which will influence your choice of material.

Staying emotionally neutral

In your academic writing, show that you can stand back and analyse evidence dispassionately, as an objective onlooker.